Tuesday 4 October 2016

Monday 3 October 2016

Advanced camera settings

Objective

To explore the camera's other settings

Task

You need to use some of the settings outlined in class. Complete a photoshoot including contact sheets that demonstrate your use of AV and TV modes and produce some (2-3) images.

Presentation

Google Slides including 2-3 images with evaluation stage to explain what you have done and how to use AV and TV settings

Deadline

2nd of OctoberThursday 29 September 2016

Daguerre

Daguerre was born in Cormeilles-en-Parisis, Val-d'Oise, France. He was apprenticed in architecture, theatre design, and panoramic painting to Pierre Prévost, the first French panorama painter. Exceedingly adept at his skill of theatrical illusion, he became a celebrated designer for the theatre, and later came to invent the diorama, which opened in Paris in July 1822.

In 1829, Daguerre partnered with Nicéphore Niépce, an inventor who had produced the world's first heliograph in 1822 and the first permanent camera photograph four years later. Niépce died suddenly in 1833, but Daguerre continued experimenting, and evolved the process which would subsequently be known as the daguerreotype. After efforts to interest private investors proved fruitless, Daguerre went public with his invention in 1839. At a joint meeting of the French Academy of Sciences and the Académie des Beaux Arts on 7 January of that year, the invention was announced and described in general terms, but all specific details were withheld. Under assurances of strict confidentiality, Daguerre explained and demonstrated the process only to the Academy's perpetual secretary François Arago, who proved to be an invaluable advocate. Members of the Academy and other select individuals were allowed to examine specimens at Daguerre's studio. The images were enthusiastically praised as nearly miraculous, and news of the daguerreotype quickly spread. Arrangements were made for Daguerre's rights to be acquired by the French Government in exchange for lifetime pensions for himself and Niépce's son Isidore; then, on 19 August 1839, the French Government presented the invention as a gift from France "free to the world", and complete working instructions were published.

In 1829, Daguerre partnered with Nicéphore Niépce, an inventor who had produced the world's first heliograph in 1822 and the first permanent camera photograph four years later. Niépce died suddenly in 1833, but Daguerre continued experimenting, and evolved the process which would subsequently be known as the daguerreotype. After efforts to interest private investors proved fruitless, Daguerre went public with his invention in 1839. At a joint meeting of the French Academy of Sciences and the Académie des Beaux Arts on 7 January of that year, the invention was announced and described in general terms, but all specific details were withheld. Under assurances of strict confidentiality, Daguerre explained and demonstrated the process only to the Academy's perpetual secretary François Arago, who proved to be an invaluable advocate. Members of the Academy and other select individuals were allowed to examine specimens at Daguerre's studio. The images were enthusiastically praised as nearly miraculous, and news of the daguerreotype quickly spread. Arrangements were made for Daguerre's rights to be acquired by the French Government in exchange for lifetime pensions for himself and Niépce's son Isidore; then, on 19 August 1839, the French Government presented the invention as a gift from France "free to the world", and complete working instructions were published.

In 1826, prior to his association with Daguerre, Niépce used a coating ofbitumen of Judea to make the first permanent camera photograph. The bitumen was hardened where it was exposed to light and the unhardened portion was then removed with a solvent. A camera exposure lasting for hours or days was required. Niépce and Daguerre later refined this process, but unacceptably long exposures were still needed.

After the death of Niépce in 1833, Daguerre concentrated his attention on the light-sensitive properties of silver salts, which had previously been demonstrated by Johann Heinrich Schultz and others. For the process which was eventually named thedaguerreotype, he exposed a thin silver-plated copper sheet to the vapor given off by iodine crystals, producing a coating of light-sensitive silver iodide on the surface. The plate was then exposed in the camera. Initially, this process, too, required a very long exposure to produce a distinct image, but Daguerre made the crucial discovery that an invisibly faint "latent" image created by a much shorter exposure could be chemically "developed" into a visible image. Upon seeing the image, the contents of which are unknown, Daguerre said, "I have seized the light – I have arrested its flight!"

The latent image on a daguerreotype plate was developed by subjecting it to the vapor given off by mercury heated to 75 °C. The resulting visible image was then "fixed" (made insensitive to further exposure to light) by removing the unaffected silver iodide with concentrated and heated salt water. Later, a solution of the more effective "hypo" (hyposulphite of soda, now known assodium thiosulfate) was used instead.

The resultant plate produced an exact reproduction of the scene. The image was laterally reversed—as images in mirrors are—unless a mirror or invertingprism was used during exposure to flip the image. To be seen optimally, the image had to be lit at a certain angle and viewed so that the smooth parts of its mirror-like surface, which represented the darkest parts of the image, reflected something dark or dimly lit. The surface was subject to tarnishing by prolonged exposure to the air and was so soft that it could be marred by the slightest friction, so a daguerreotype was almost always sealed under glass before being framed (as was commonly done in France) or mounted in a small folding case (as was normal in the UK and US).

Daguerreotypes were usually portraits; the rarer landscape views and other unusual subjects are now much sought-after by collectors and sell for much higher prices than ordinary portraits. At the time of its introduction, the process required exposures lasting ten minutes or more for brightly sunlit subjects, so portraiture was an impractical ordeal. Samuel Morse was astonished to learn that daguerreotypes of the streets of Paris did not show any people, horses or vehicles, until he realized that due to the long exposure times all moving objects became invisible. Within a few years, exposures had been reduced to as little as a few seconds by the use of additional sensitizing chemicals and "faster" lensessuch as Petzval's portrait lens, the first mathematically calculated lens.

The daguerreotype was the Polaroid film of its day: it produced a unique image which could only be duplicated by using a camera to photograph the original. Despite this drawback, millions of daguerreotypes were produced. The paper-based calotype process, introduced by Henry Fox Talbot in 1841, allowed the production of an unlimited number of copies by simple contact printing, but it had its own shortcomings—the grain of the paper was obtrusively visible in the image, and the extremely fine detail of which the daguerreotype was capable was not possible. The introduction of the wet collodion process in the early 1850s provided the basis for a negative-positive print-making process not subject to these limitations, although it, like the daguerreotype, was initially used to produce one-of-a-kind images—ambrotypes on glass and tintypes on black-lacquered iron sheets—rather than prints on paper. These new types of images were much less expensive than daguerreotypes, and they were easier to view. By 1860 few photographers were still using Daguerre's process.

The same small ornate cases commonly used to house daguerreotypes were also used for images produced by the later and very different ambrotype andtintype processes, and the images originally in them were sometimes later discarded so that they could be used to display photographic paper prints. It is now a very common error for any image in such a case to be described as "a daguerreotype". A true daguerreotype is always an image on a highly polished silver surface, usually under protective glass. If it is viewed while a brightly lit sheet of white paper is held so as to be seen reflected in its mirror-like metal surface, the daguerreotype image will appear as a relatively faint negative—its dark and light areas reversed—instead of a normal positive. Other types of photographic images are almost never on polished metal and do not exhibit this peculiar characteristic of appearing positive or negative depending on the lighting and reflections.

Competition with Talbot

Unbeknownst to either inventor, Daguerre's developmental work in the mid-1830s coincided with photographic experiments being conducted by Henry Fox Talbot in England. Talbot had succeeded in producing a "sensitive paper" impregnated with silver chloride and capturing small camera images on it in the summer of 1835, though he did not publicly reveal this until January 1839. Talbot was unaware that Daguerre's late partner Niépce had obtained similar small camera images on silver-chloride-coated paper nearly twenty years earlier. Niépce could find no way to keep them from darkening all over when exposed to light for viewing and had therefore turned away from silver salts to experiment with other substances such as bitumen. Talbot chemically stabilized his images to withstand subsequent inspection in daylight by treating them with a strong solution of common salt.

When the first reports of the French Academy of Sciences announcement of Daguerre's invention reached Talbot, with no details about the exact nature of the images or the process itself, he assumed that methods similar to his own must have been used, and promptly wrote an open letter to the Academy claiming priority of invention. Although it soon became apparent that Daguerre's process was very unlike his own, Talbot had been stimulated to resume his long-discontinued photographic experiments. The developed out daguerreotype process only required an exposure sufficient to create a very faint or completely invisible latent image which was then chemically developed to full visibility. Talbot's earlier "sensitive paper" (now known as "salted paper") process was aprinted out process that required prolonged exposure in the camera until the image was fully formed, but his later calotype (also known as talbotype) paper negative process, introduced in 1841, also used latent image development, greatly reducing the exposure needed, and making it competitive with the daguerreotype.

Daguerre's agent Miles Berry applied for a British patent just days before France declared the invention "free to the world". Great Britain was thereby uniquely denied France's free gift, and became the only country where the payment of license fees was required. This had the effect of inhibiting the spread of the process there, to the eventual advantage of competing processes which were subsequently introduced. Antoine Claudet was one of the few people legally licensed to make daguerreotypes in Britain. Daguerre's pension was relatively modest—barely enough to support a middle-class existence—and apparently this British "irregularity" was allowed to pass without adverse consequences or much comment outside of the UK.

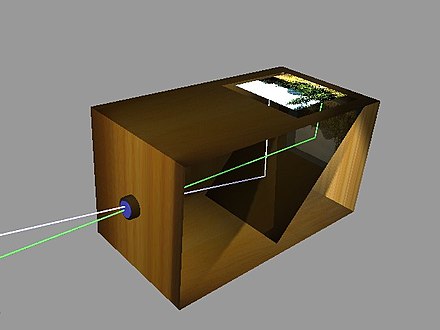

Camera Obscura

A camera obscura (Latin: "dark chamber") is an optical device that led to photography and the photographic camera. The device consists of a box or room with a hole in one side. Light from an external scene passes through the hole and strikes a surface inside, where it is reproduced, rotated 180 degrees (thus upside-down), but with color and perspectivepreserved. The image can be projected onto paper, and can then be traced to produce a highly accurate representation. The largest camera obscura in the world is on Constitution Hill in Aberystwyth, Wales.

Using mirrors, as in an 18th-century overhead version, it is possible to project a right-side-up image. Another more portable type is a box with an angled mirror projecting ontotracing paper placed on the glass top, the image being upright as viewed from the back.

As the pinhole is made smaller, the image gets sharper, but the projected image becomes dimmer. With too small a pinhole, however, the sharpness worsens, due to diffraction. Most practical camera obscuras use a lens rather than a pinhole (as in a pinhole camera) because it allows a largeraperture, giving a usable brightness while maintaining focus.

History of photography

The history of photography has roots in remote antiquity with the discovery of the principle of the camera obscura and the observation that some substances are visibly altered by exposure to light. As far as is known, nobody thought of bringing these two phenomena together to capture camera images in permanent form until around 1800, when Thomas Wedgwood made the first reliably documented although unsuccessful attempt. In the mid-1820s, Nicéphore Niépce succeeded, but several days of exposure in the camera were required and the earliest results were very crude. Niépce's associate Louis Daguerre went on to develop the daguerreotypeprocess, the first publicly announced photographic process, which required only minutes of exposure in the camera and produced clear, finely detailed results. It was commercially introduced in 1839, a date generally accepted as the birth year of practical photography.

The metal-based daguerreotype process soon had some competition from the paper-based calotype negative and salt print processes invented by Henry Fox Talbot. Subsequent innovations reduced the required camera exposure time from minutes to seconds and eventually to a small fraction of a second; introduced new photographic media which were more economical, sensitive or convenient, including roll films for casual use by amateurs; and made it possible to take pictures in natural color as well as in black-and-white.

The commercial introduction of computer-based electronic digital cameras in the 1990s soon revolutionized photography. During the first decade of the 21st century, traditional film-based photochemical methods were increasingly marginalized as the practical advantages of the new technology became widely appreciated and the image quality of moderately priced digital cameras was continually improved.

Tuesday 13 September 2016

Henri Cartier Bresson

Objective

To create a blog post that demonstrates your ability to analyse the work of Henri Cartier Bresson

To create a blog post that demonstrates your ability to analyse the work of Henri Cartier Bresson

Task.

You will need to create a post that demonstrates your Ability to analyse images from famous photographers

- Make some pages in your google slide that analyses the work of Henri Cartier Bresson.

- You need to include around 3 of his images and use the techniques discussed in class

- You will then need to use his style in your own work and produce at least 3 images of our own

Presentation

Your work should look amazing, make sure your images are large and that you separate your own work from the work of artists. Make sure you credit the artists work and that you include contact sheets.

Deadline

25th of September

Friday 9 September 2016

Camera Settings

Shutter speed

The shutter in a camera can be adjusted to let more or less light onto the light sensitive substrate. Shutter settings can be set to a fast value - 1000th of a second or higher, or a low value - a 30th of a second down to 30 seconds (or 6 months).There are 2 effects to adjusting shutter speed in a camera:

- Exposure - how light or dark the image is

- Motion blur - how sharp movement can be captured by the camera

A slow shutter speed (30th of a second 1/30) will be brighter, and blurrier, than a photo taken at a higher shutter speed (1000th of a second 1/1000). This will only be true if all other settings remain the same. You can maintain exposure by compensating other settings.

Aperture

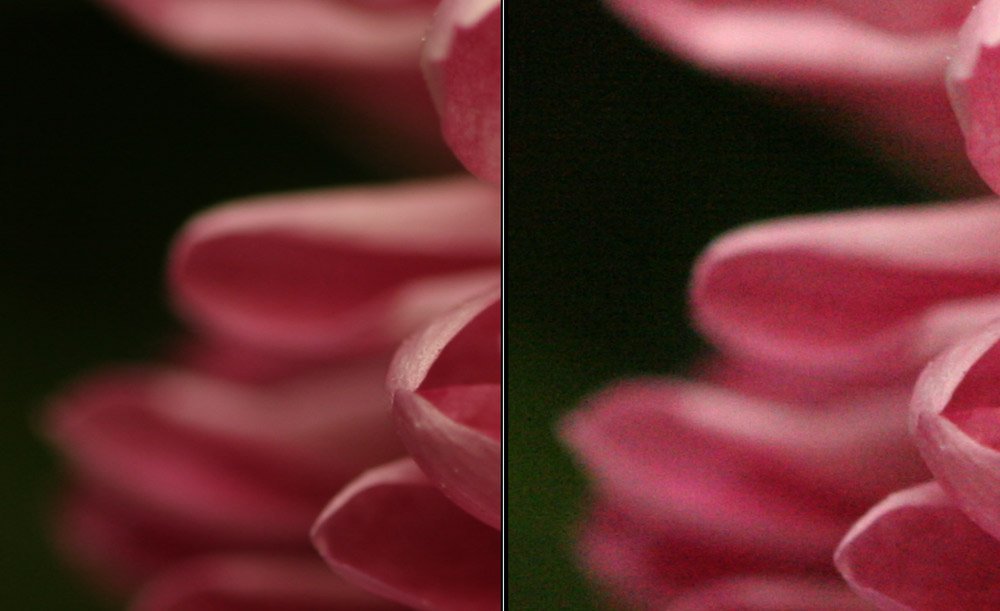

The aperture in a camera can be adjusted to let more or less light onto the light sensitive substrate. Aperture values can be set high - f22, or low - f1.8 and all values in between.

There are 2 effects of adjusting the aperture in a camera, these are

- Exposure - how light or dark the image is

- Depth of field - how much of the comparative distance remains in focus.

A high aperture value (f22) makes your image darker and both distant and close up objects remain in focus. A low aperture value (f1.8) makes your image brighter and your focus becomes shallower, you will only be able to focus on objects that are far away or close up, not both. The exposure will only be affected if other settings are not changed, you may compensate exposure by adjusting shutter speed in the opposite direction.

ISO

The ISO setting in a camera can be adjusted to change the sensitivity of the light sensitive substrate. ISO values can be set high - 3200, or low - 100 and all values in between.

There are 2 effects of adjusting the aperture in a camera, these are

- Exposure - how light or dark the image is

- Grain/noise - how clear the image is overall

A high ISO value 3200 makes your image lighter and creates more noise. A low ISO value 100 makes your image darker and your image will become clearer. The exposure will only be affected if other settings are not changed, you may compensate exposure by adjusting shutter speed or aperture in the opposite direction. ISO will help enable you to adjust other settings if the subject remains too bright or too dark; for example, if you need to capture a fast moving object in limited lighting conditions and already have the lowest aperture settings you may need to increase you ISO if the image results are too dark.

Objective

To create a few pages that demonstrates your understanding of the use of various camera settings

To create a few pages that demonstrates your understanding of the use of various camera settings

Task.

You will need to create a post that demonstrates your understanding of the use of Camera controls, you will need to

- Post 2 images found on the internet, or other secondary source, that demonstrates the use of adjusting each setting on the camera. (6 images in total)

- Post 2 images of your own work for each setting that demonstrates your understanding of the use of the different camera controls

Presentation

Your work should look amazing, make sure your images are large and that you separate your own work from the work of artists. Make sure you credit the artists work and that you include contact sheets. You need to complete at least 3 different pages on your presentation, one for each of the camera settings.

Deadline

18th of September

Tuesday 6 September 2016

Thursday 1 September 2016

The classic design elements

Objective

To create at least 6 pages that demonstrates your understanding the compositional/artistic elements

Task.

You will need to create a post that demonstrates your understanding of the use of the compositional and artistic elements discussed in class

- Post 3 images from the internet that you like and analyse them using the information discussed in class on the classic design elements

- Take 3 images of your own and put them on the blog with your own explanation of why you have taken that photo. analyse the photos making sure you use the information on the elements discussed in class.

Presentation

The work should be at least 6 pages with the title 'photographic analysis' or 'analysis', and contain images and written work. You will spend lesson time finding images and take your own pictures at home or in free periods,

Deadline

14th of September

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)